A few weeks ago I started a project to set up a new home for my various web projects in the AWS cloud. All these sites use WordPress, and I wanted to make sure I built them on a robust and scalable architecture.

The tricky thing with WordPress is that it was designed around a traditional web server model, where one physical (or virtual) machine serves one instance of the code. When you update themes or plugins, or upload content, you change the data on that instances’s locally attached storage. I wanted to be able to horizontally scale, and WordPress’s design makes that difficult.

Horizontal scaling is achieved by adding additional server instances to spread the load, whereas vertical scaling relies on beefing up the one machine with more CPU or memory. Horizontal scaling is generally preferable, because it not only provides more flexible scaling, eg you can scale up during periods of peak demand, and scale back down later, but because it gives you the added benefit of redundancy – if I have three machines serving my web sites, I can have two die and still be online, albeit perhaps in a degraded state.

To achieve this horizontal scaling in AWS, we need a way to have many machines share the same set of code. Amazon’s Elastic File System allows us to do that by providing an NFSv4 compatible file system that can be mounted simultaneously to many EC2 instances. All the instances can read and write the same filesystem – problem solved.

So, I built a machine image for my WordPress solution that, on boot, would update itself and mount the EFS volume, ready to serve the shared code within. I set up an autoscaling group and an Application Load balancer to distribute traffic to them. I moved my domains to Route53 bound them via aliases to the LB’s AWS resource name. I used Amazon Certificate Manager to create (free!) SSL certificates that are automatically bound to the LBs. I backed this WordPress Taj Mahal with an Aurora RDS instance and enabled Cloudfront as a CDN.

It was all too easy, and the result was exactly what I wanted. I sat back feeling smug.

Of course, that didn’t last long. A few days ago I got a Pingdom alert saying a site was down. Then another, and another…what was going on?

I went online to check…”Bad Gateway 504″. Oh crap. Hm.

So what was failing? EC2 instances? Load balancer? Some weird WordPress problem? I checked them all and was none the wiser. Unfortunately for me, this happened at 8am on a workday, so I had to leave everything in a broken state and come back to it later.

When I logged in later, I noticed that requests to read the content on the EFS volume mounted on the EC2 instances took a long time to respond – several seconds in some cases. Hm, dodgy EFS? Nope, all the data seemed fine and there was nothing in the EFS console that looked like an alarm.

So, I tried that classic IT trick of turning it on and off again. I rebooted EC2 instances, I unmounted and remounted the volumes…nothing helped.

Having exhausted all the other possibilities, I concluded that the EFS performance issue had to be the cause of all my problems, so I posted an issue with AWS support. The next morning, I had my answer.

“You’ve run out of EFS Burst Credits.”

Huh?

So, I guess I hadn’t been paying as much attention as I should and this detail had passed me by…EFS volumes have “Burst Credits” that are calculated based on the size of the data stored on them. And it seems when you run out of burst credits, you can expect your EFS volume’s performance to suck badly enough that your whole system can fail.

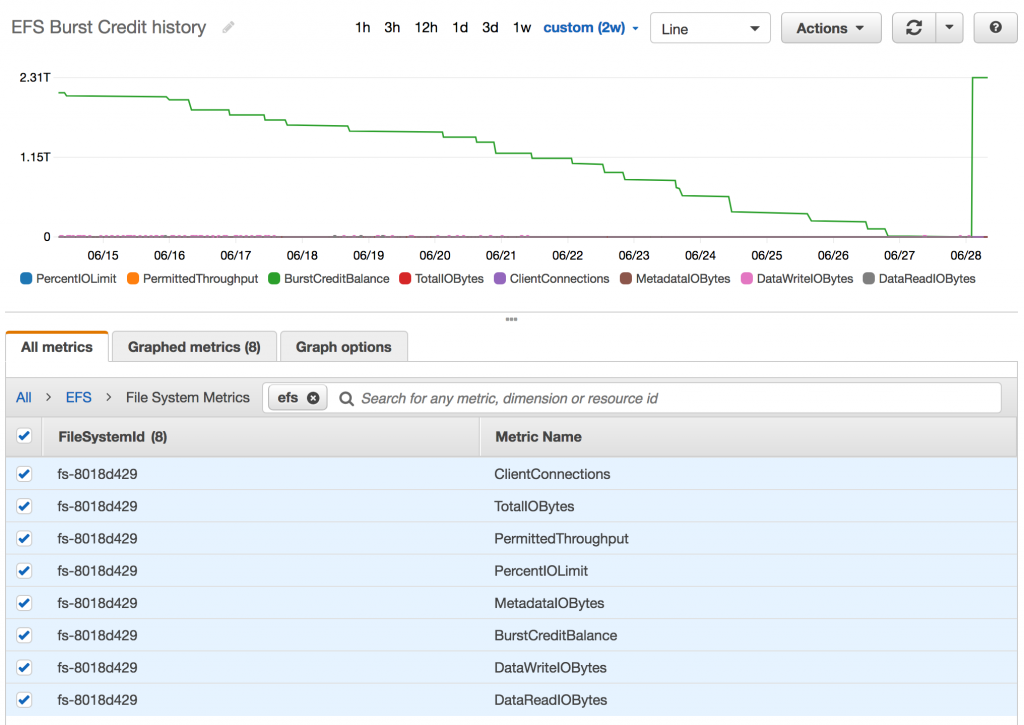

Here’s how my EFS burst credit level dropped over the preceding two weeks:

As my EFS volume is under a GB in size, it generates very little in the way of burst credits. You can check out the details here.

You can also see here that it’s the ONLY metric that mattered. And boy, did it cause me some grief.

So, my new plan is to keep using EFS, but to use rsync, on boot, to clone the data from the EFS mount to the locally attached EBS volume and use that as the web server’s document root. I’ll leave rsync running to watch both the local and the EFS filesystems for changes and to keep them in sync.

Note to the folks at AWS – put the burst credit metric on the EFS console! Don’t make schmucks like me find out the hard way!